Connecting Pixels and Theme Parks Part 1: Attraction Design and Thirty Flights of Loving (2012)

- Blog Posts

The crossover between theme park design and video game design is no secret. Besides sharing many of the same fans and, more recently, intellectual properties, both are unique among art forms in that they require a degree of audience agency to navigate their spaces and advance their stories. However, because absolute freedom of agency would be nearly impossible to combine with effective storytelling, both theme park designers and game designers each have their own set of tools and techniques to help guide players or guests through their story-worlds in ways that are both efficient and entertaining.

How do you control viewsheds so people will be clued in on where to go next in what’s otherwise an open-world environment? How do you make that mountain appear bigger or further away than it actually is? When do you give people more agency, and when do you want to restrict them through a carefully crafted story beat?

As a theme park designer, it’s always exciting to play a video game and recognize techniques we use in our practical environments inside a virtual game environment. We even often look to video games for inspiration in solving some of our own design challenges.

There are two games in particular that I often find myself referencing when I think about what qualities could signal the future of theme park design; the first in relation to linear storytelling as on a dark ride, the second in relation to environmental storytelling as in a themed land. Both are relatively experimental independent titles that buck many of the established norms of gameplay and storytelling, and I highly recommend both whether you’re interested in theme park or video game design or simply looking for a fun distraction while we’re all trying to socially distance.

* * *

The first of these games is Thirty Flights of Loving, which debuted in 2012 by Blendo Games (essentially a one-man effort by Brendon Chung), self-described as a “Video Game Short Story”:

The game takes approximately fifteen minutes to complete, and is almost entirely linear with extremely limited player agency; you can decide when to move forward, but not how to move forward. It tells the story of a budding yet potentially dangerous romance at the center of a planned airport heist that goes wrong. Although told entirely from a first-person POV, Thirty Flights of Loving wears its cinematic influences on its sleeve, in particular the work of Wong Kar-wai (Chungking Express, Ashes of Time), with its nonlinear storyline, bold color palette, inventive choreography, and elusive narrative that combines popular genre storytelling with arthouse flair.

Yet the limited agency it does afford to the player’s first-person perspective is essential to making this more than just a first-person short film. I feel more invested in the fate of the characters, even if that fate is ultimately out of my hands. The self-directed pace allows me to linger over small details that build the world during slower-paced scenes. A similar effect plays out in dark ride attraction design. Even though I have no control over which direction the vehicle goes, I do feel some responsibility within the story because I’m not removed to a third-person perspective like I am in cinema. I must have played through Thirty Flights of Loving at least a dozen times. Individual scenes played out with intoxicating precision and emotional clarity, yet reassembling the entire non-linear storyline left me with more questions than answers. Of course, like a good dark ride, this encouraged me to experience it again to find alternate interpretations.

After a couple of plays, I realized that the structure of the game could be almost perfectly adapted as an attraction design for a dark ride.

It begins with a long queue-like passageway through several connected rooms into a hidden safehouse, all of which conveys essential exposition about the characters and world they inhabit, through techniques familiar to theme park fans: “found” objects and props laid out in a deliberately sequential order, framed news clippings to pause and read, even a short “preshow” animated sequence introducing the two primary supporting characters. (In a developer commentary, Chung even directly states his influence by theme park design techniques such as forced perspective to build these sets in digital space.) The intro sequence ends when you climb inside a seaplane (like a ride vehicle) and you’re immediately launched into the narrative action.

It begins with a long queue-like passageway through several connected rooms into a hidden safehouse, all of which conveys essential exposition about the characters and world they inhabit, through techniques familiar to theme park fans: “found” objects and props laid out in a deliberately sequential order, framed news clippings to pause and read, even a short “preshow” animated sequence introducing the two primary supporting characters. (In a developer commentary, Chung even directly states his influence by theme park design techniques such as forced perspective to build these sets in digital space.) The intro sequence ends when you climb inside a seaplane (like a ride vehicle) and you’re immediately launched into the narrative action.

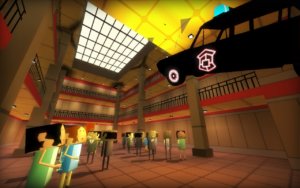

Likewise, once things come to a (literal) crashing halt at the end of the main narrative, you’re unexpectedly thrown into a museum hallway filled with “artifacts” from the story, which you wander through, free to chew over some of the lingering questions these exhibits present, or to just rush straight to the final endpoint. One would expect the theme park version to contain a gift shop in this exit corridor, but putting that aside, this slightly surreal sequence does provide inspiration for how an exit corridor could be used as the true “final beat” of an attraction’s storyline, and not just a means to return guests to the midway.

As for that main narrative, its brevity and elusiveness is perhaps why I find it such a compelling parallel to dark ride storytelling. Trying to tell a complete story in a few minutes across a limited number of scenes is tough, and many dark rides fall into the trap of trying to condense a story by stripping everything down to the narrative’s bones, resulting in an experience that can feel hurried and confusing. Thirty Flights of Loving, by contrast, borrows the lessons of successful short fiction by using its limited time to establish tone and emotional pacing amid what’s otherwise an exceedingly simple story of a tragic romance. For all its crazy action, the scene I best remember takes place in the early dawn light as the lead characters silently share a box of tangerines on a balcony… a communal moment of tranquility the game’s designer included to recall his own memories of sharing tangerines with family.

As for that main narrative, its brevity and elusiveness is perhaps why I find it such a compelling parallel to dark ride storytelling. Trying to tell a complete story in a few minutes across a limited number of scenes is tough, and many dark rides fall into the trap of trying to condense a story by stripping everything down to the narrative’s bones, resulting in an experience that can feel hurried and confusing. Thirty Flights of Loving, by contrast, borrows the lessons of successful short fiction by using its limited time to establish tone and emotional pacing amid what’s otherwise an exceedingly simple story of a tragic romance. For all its crazy action, the scene I best remember takes place in the early dawn light as the lead characters silently share a box of tangerines on a balcony… a communal moment of tranquility the game’s designer included to recall his own memories of sharing tangerines with family.

“Story” is more than just a narrative, and the game’s focus on crafting emotionally resonant moments within a narrative structure that could be rearranged like a Rubik’s cube is what kept me coming back, again and again. And that kind of repeatability is what every attraction design should aspire to.

If Thirty Flights of Loving provided an inspired insight into linear interactive storytelling within the relatively compact confines of attraction design, the next part will examine a very different game for inspiration on the expansive open possibilities of design for an entire theme park. Look for the second half of this series to be published next week!

Related Posts

Thinkwellians Win Accolades

- Blog Posts

- News

- Subject Matter Expert

Thinkwell (a TAIT company) congratulates its team members Thomas Jakobson...

Embracing AI

- Blog Posts

Whether we like it as a tool or fear that...

Welcome to Kansas City!

- Blog Posts

Welcome, TEA, to my stomping grounds. Yeah, I’m a Chicagoan...