Since the start of the pandemic in March of 2020, we all have gone through a lot. Whether it was missing a family reunion, an anniversary cruise, a vacation with best friends, or simply a special dinner out. What all these things have in common is the one thing we didn’t know we were going to miss: anticipation.

From the American Psychological Association: Anticipation is a state of expectation or excitement about an upcoming event or situation. It is a state of suspense and expectancy. For example, when you know an old friend is going to drop by you probably are in a state of anticipation while waiting for them–you are excited, maybe a little nervous, and filled with expectations about their visit.

Before the pandemic, our lives were full of anticipation. Upcoming movie releases, lunch with a colleague, a trip to the museum, a dinner with a loved one, a pending concert. These things all slowly (and quickly!) ended. Restaurants closed so reservations were canceled. Concerts that were months away became unceremonious credit card refunds. Family vacations turned into airline vouchers and cancellation emails from hotels and rental car companies.

But we need anticipation. The very nature of that feeling is all about future reward, and right now, almost more than many other things, we deserve a reward. From lunch to travel, anticipation is the bringer of excitement, the harbinger of adventure, or simply the feeling that we are going to be doing something unmapped, uncharted, and different. Anticipation often includes daydreaming, research, and planning.

The Doblin Group, an innovation consultancy based in Chicago, codified compelling experiences. Their research showed that one of the key attributes to any compelling experience is the first of three phases, attraction. “Attraction” referred to the build-up to the experience itself, notably research, planning, and daydreaming. In other words, anticipation.

Kelsey Borresen, a Senior Reporter with Huffpost wrote a piece last year called, “The Psychological Benefits of Having Something to Look Forward To.” In it, she wrote:

Research suggests that living in the present moment and practicing mindfulness can increase happiness.

“However, during particularly stressful moments in time, like our current pandemic, it can be more beneficial to have something to look forward to,” said Atlanta therapist LeNaya Smith Crawford.

Anticipation, in many ways, is hope for the future. That state of suspense and expectancy is now its own ecstasy, an ecstasy we are can control. “It is the implicit knowing that positive emotion will happen in the future,” says Guy Kuchnick, a New York psychologist and founder of Techhealthiest. According to research published in the journal Psychological Science, planning your itinerary, booking tickets, and anticipating a vacation can boost your mood long before you step on a plane.

We’ve been stressed. We need anticipation.

Theme parks are open or are opening up. Vaccines are moving through their phases and the CDC’s guidelines for gathering are loosening as a result. Local jurisdictions are allowing, in many cities, for restaurants to open indoor dining again.

All these things bring hope because they are the impetus of anticipation.

Airlines and cruise lines have better, more flexible cancellation policies now than in the past. Maybe not tomorrow, but soon, we can journey again. Why not enter that “Attraction” phase of any compelling experience and start researching your next vacation, plan that cruise, start organizing the next family reunion, or simply consider where the first place will be when you go out to dinner again?

Let’s bring back anticipation.

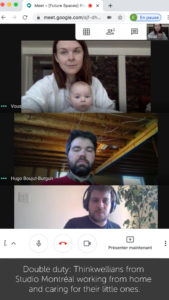

When we shift the topic of our lockdown experiences away from work-related things, however, the conversation takes a revealing turn. When asked what happy surprises our suddenly homebound existences have revealed after these many months, our answers are notably intimate and personal. Many of us take great satisfaction in finally checking off items on our much ignored to do lists, ignored not so much because we’ve been busy, but because we had so many ready distractions to blame for our procrastination. My colleagues have fixed that leaky faucet, renovated a room, completed unfinished writing projects, honed new skills, created the artwork, crafted instruments, miniatures, sweaters, scarves, and quilts. Others have tended their gardens, harvested their crops, and prepared their meals… and spent time with each other.

When we shift the topic of our lockdown experiences away from work-related things, however, the conversation takes a revealing turn. When asked what happy surprises our suddenly homebound existences have revealed after these many months, our answers are notably intimate and personal. Many of us take great satisfaction in finally checking off items on our much ignored to do lists, ignored not so much because we’ve been busy, but because we had so many ready distractions to blame for our procrastination. My colleagues have fixed that leaky faucet, renovated a room, completed unfinished writing projects, honed new skills, created the artwork, crafted instruments, miniatures, sweaters, scarves, and quilts. Others have tended their gardens, harvested their crops, and prepared their meals… and spent time with each other.

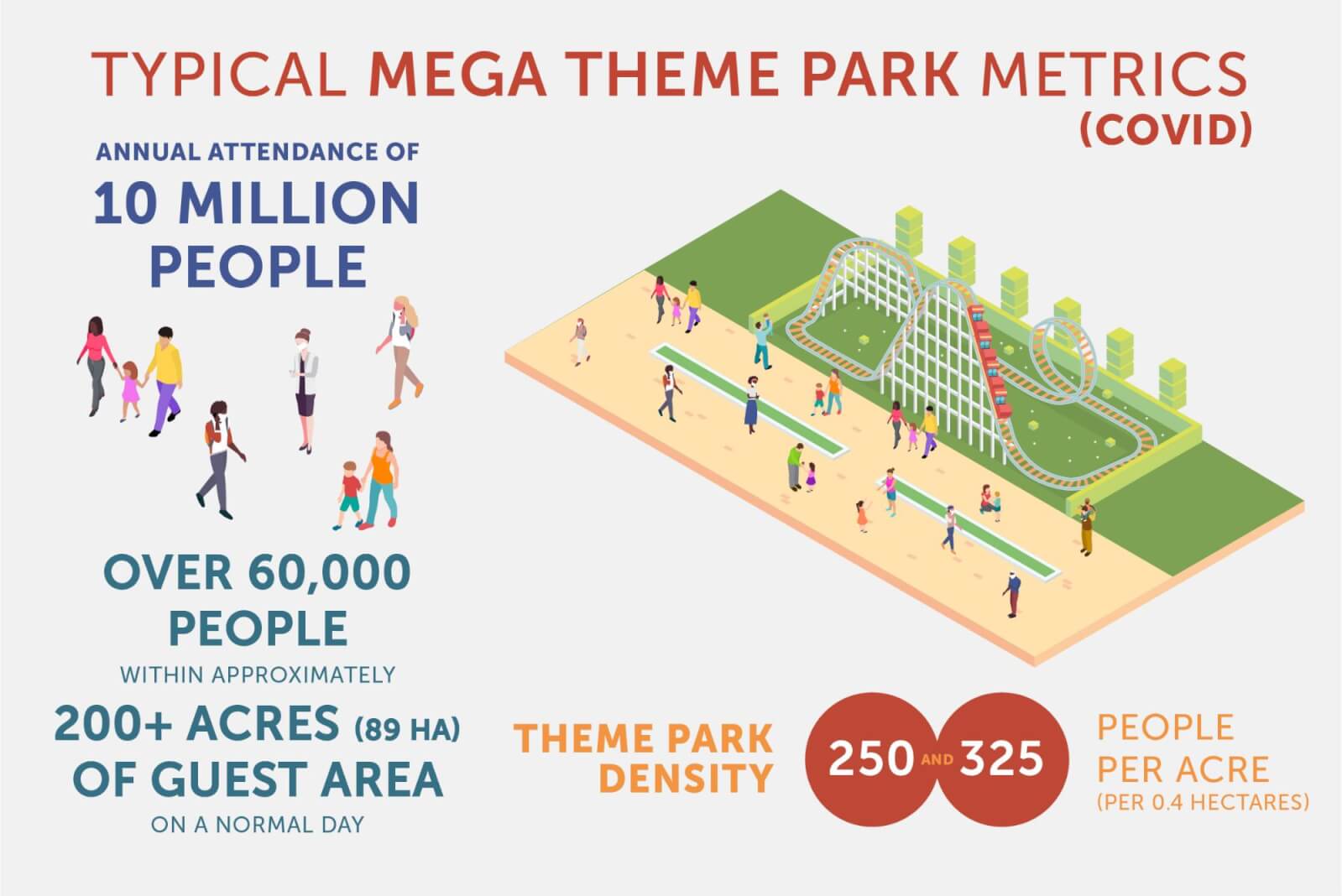

Disney Shanghai has opened its doors at reduced capacity to allow visitors space to learn the “new norms”, such as spacing out within a queue and frequent hand sanitizing and facility wipe downs. A “mega theme park” like the Disney or Universal parks typically means an annual attendance of over 10 million people, and over 60,000 people within approximately 110 acres of guest area on a normal day.

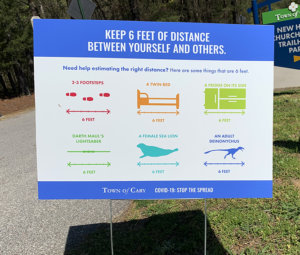

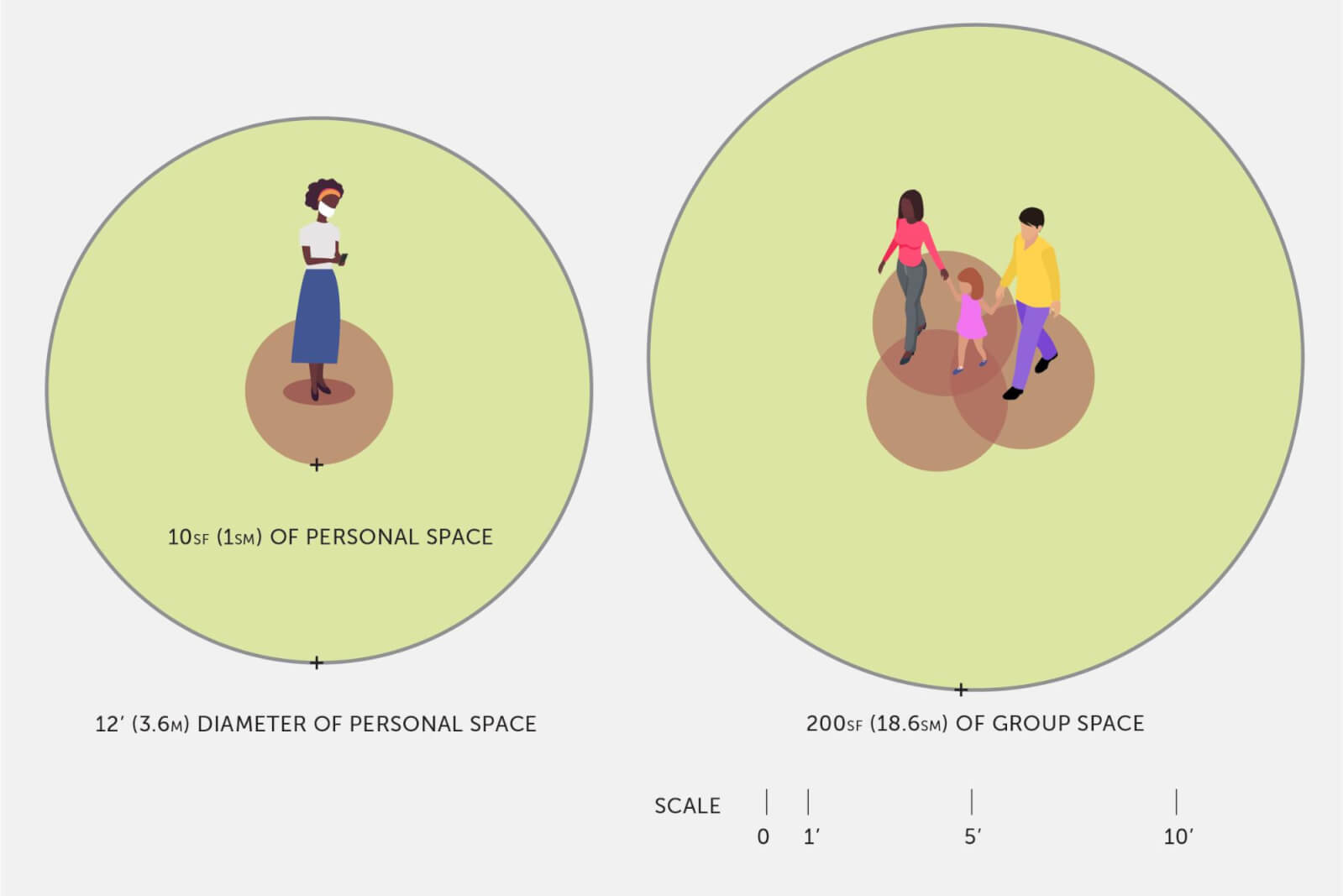

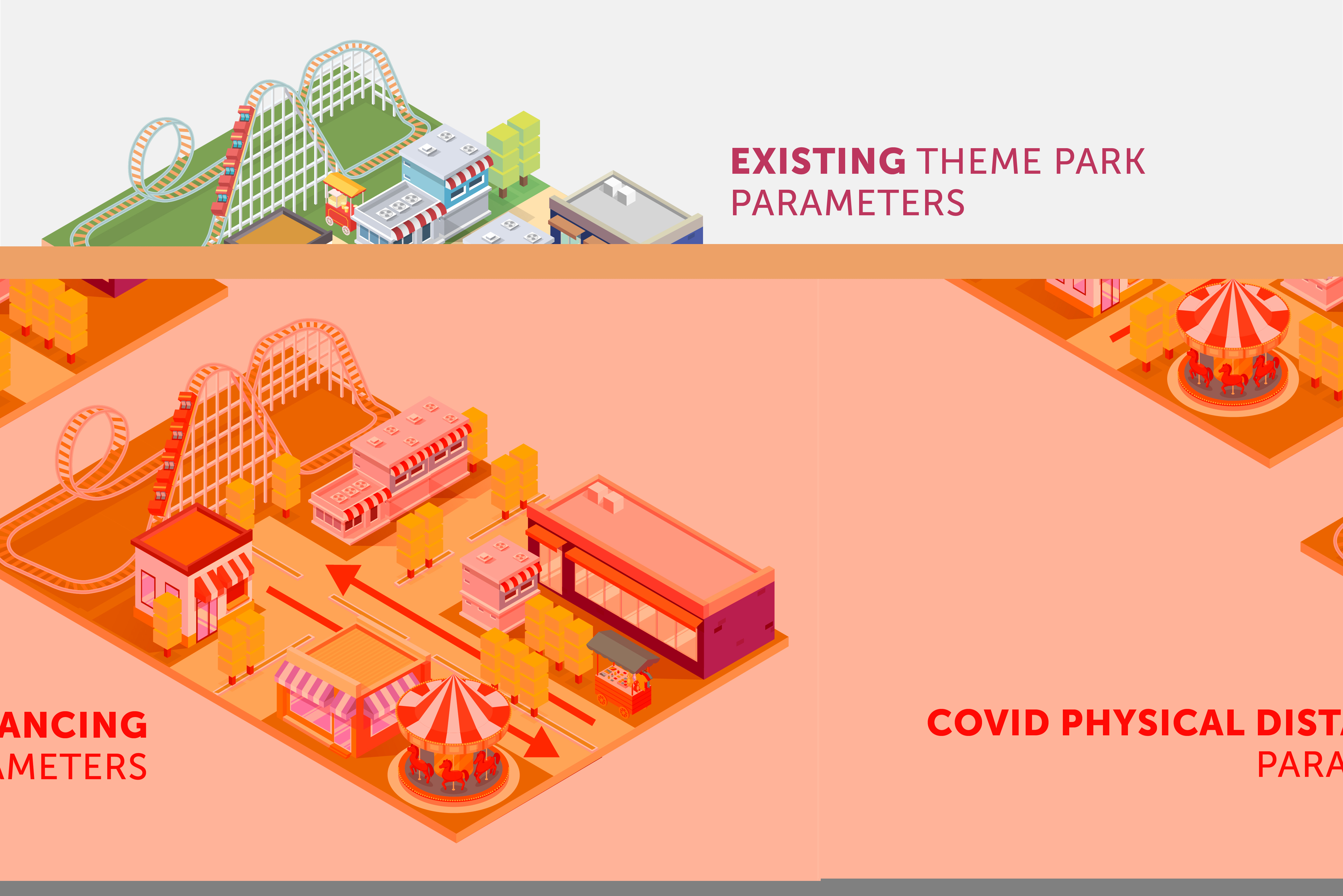

Disney Shanghai has opened its doors at reduced capacity to allow visitors space to learn the “new norms”, such as spacing out within a queue and frequent hand sanitizing and facility wipe downs. A “mega theme park” like the Disney or Universal parks typically means an annual attendance of over 10 million people, and over 60,000 people within approximately 110 acres of guest area on a normal day.  Space is the major commodity when talking about physical distancing. During a typical summer weekend day at a theme park, visitors often find themselves walking in a crowd, frequently having to stop momentarily or making frequent course corrections to avoid bumping others. This indicates a density of 10-15 square feet, sf (1-1.4 square meters, sm) per person within the circulation space, and if there’s a parade or a sudden character appearance, that density may go down to 5 sf (0.46 sm) per person, meaning that people will be brushing into each other and their movement will be severely restricted until the gathering disperses. These factors are what drive many theme parks to create “travel lanes” around parades or performance areas to allow the movement of people to still flow, albeit still at a reduced rate.

Space is the major commodity when talking about physical distancing. During a typical summer weekend day at a theme park, visitors often find themselves walking in a crowd, frequently having to stop momentarily or making frequent course corrections to avoid bumping others. This indicates a density of 10-15 square feet, sf (1-1.4 square meters, sm) per person within the circulation space, and if there’s a parade or a sudden character appearance, that density may go down to 5 sf (0.46 sm) per person, meaning that people will be brushing into each other and their movement will be severely restricted until the gathering disperses. These factors are what drive many theme parks to create “travel lanes” around parades or performance areas to allow the movement of people to still flow, albeit still at a reduced rate.

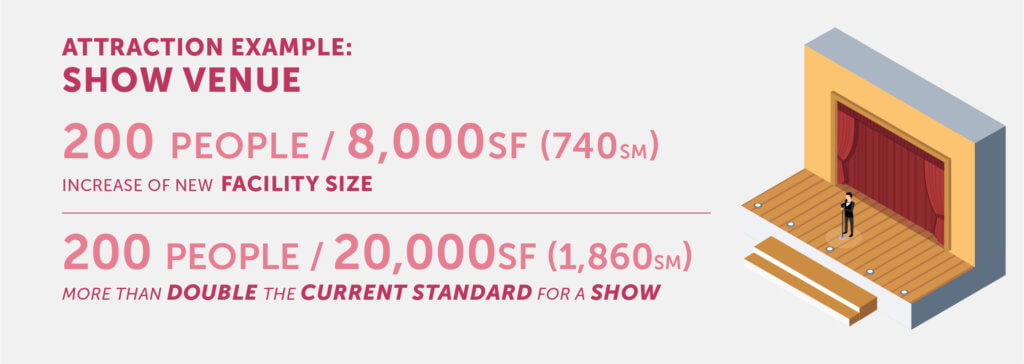

From a simple space planning perspective focusing on the physical distancing recommendations, the theme park circulation will have to increase 100%, the retail by 180%, food service by 150%, and attraction areas from 150-200%. These factors, applied to

From a simple space planning perspective focusing on the physical distancing recommendations, the theme park circulation will have to increase 100%, the retail by 180%, food service by 150%, and attraction areas from 150-200%. These factors, applied to

At Thinkwell’s

At Thinkwell’s