Safety is the top concern of the attractions industry. Not only is it the foremost legal, ethical, and moral responsibility to ensure that no guest is at risk of being harmed at an attraction, but the highest standard of safety facilitates every other aspect of the guest experience as well. Designers and operators strive to create not just physically safe, but emotionally safe environments for their guests.

When COVID-19 struck, the industry applied its decades of experience in safety design to quickly implement new health and sanitation procedures for theme parks and visitor attractions, in many cases completely re-imagining their operations within a matter of months, if not weeks. So far, the data has indicated that primarily outdoor amusements that responsibly enforce these new guidelines have kept transmissions to a minimum, with no major reported outbreaks traced back to a theme park for the several months they’ve been open (as of this writing).

Yet if the focus has been on creating a physically safe environment, many operators are also having to contend with what it truly means to create an emotionally safe space for their guests. While these attractions have always emphasized that their guests have a shared responsibility for their own safety and the safety of those around them, the majority of guests returning during this pandemic are for the first time now keenly aware that a theme park is no longer an inherently safe space for them. While there are plenty of ideas for how to rebuild that previous sense of emotional reassurance under these new conditions, many guests and professionals are finding the most reassurance in the idea that, hopefully, sooner than later, everything will be completely “back to normal.”

It’s an understandable sentiment given how short supply we’ve been for reassurances recently. In fact, mitigating that anxiety and getting back to a sense of emotional safety and trust is a key part of soothing jittery would-be visitors. Nevertheless, it’s important to question that instinct for normalcy, and ask ourselves if this transformational moment in history hasn’t revealed certain fault lines in the pre-pandemic perspective of “physical and emotional safety” that… maybe… shouldn’t fully go back to the ways of the “once-normal”?

This conversation is not just limited to entertainment. As people everywhere find their sense of security and safety rocked in a way they’ve never encountered, many of them are questioning what it means to be physically and emotionally safe in public spaces of all kinds… and realizing that for many of their peers, these places have never felt for themselves completely safe to begin with.

It’s no coincidence that, during the pandemic, thousands of Black Lives Matter protestors took to the streets demanding racial justice. There is a known direct correlation between the lack of public health safety for BIPOC people and the current COVID-19 pandemic. (Over 1,000 health professionals signed a letter in support of the protests, arguing that systemic racism was an equally urgent risk to public health.) These systemic injustices, too often overlooked by society, were laid bare by the pandemic and its societal response for the entire world to witness. Protestors were demonstrating to demand safety for BIPOC folks in their everyday lives, and to take action to ensure a safer, more just world, even after the pandemic is over.

The themed entertainment industry is not isolated from this. As professionals who are privileged to create these experiences for our guests, we also need to ask: what isn’t being reflected in the standard safety data, either because it’s a less quantifiable form of emotional safety, or because marginalized groups are selected out of the data pool to begin with?

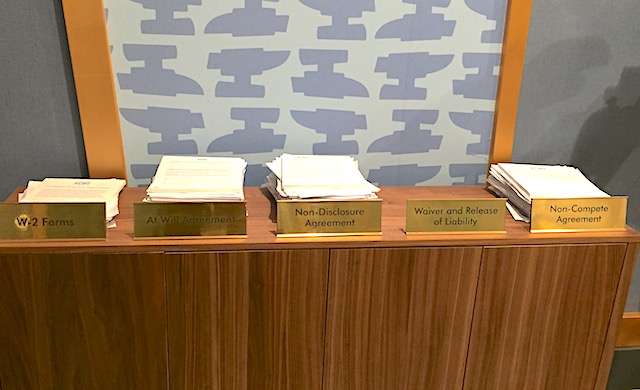

To ensure that we are creating physically and emotionally safe experiences for everyone, we must expand the definition of safety such that it is anti-racist, anti-ablist, radically inclusive, and intersectionally focused. If an attraction notices that its visitor demographics are mismatched from its local community demographics, not only should it investigate potential systemic factors like pricing structures or transportation access that could limit certain groups’ participation, but it should also review softer aspects related to design and public messaging, which very often can unintentionally code a space as “intended for” or “centered around” a certain kind of audience. Or, if those previously marginalized groups are showing up to buy a ticket but the attraction is now struggling to safely accommodate an increase in disabled and neurodiverse guests, it may need to reevaluate some of its foundational design assumptions about ride vehicles, guest flow patterns, restrooms, and restaurants alongside reviewing operational procedures and employee training.

As designers who are often at the start of the process of figuring out how these attractions look and function, we must grapple with questions of safety from an intersectional approach, not only considering the checklists we’d apply to meet all physical safety requirements, but also to the emotional and psychological well-being of guests in experiences we create. We as experience designers have to think about the intersection of public health, physical safety, and the psycho-emotional wellbeing of all guests, whether at a theme park, museum, retail and dining district, or live event. COVID has reminded us that we’re all responsible for each other’s safety, and that means every single individual within our community.

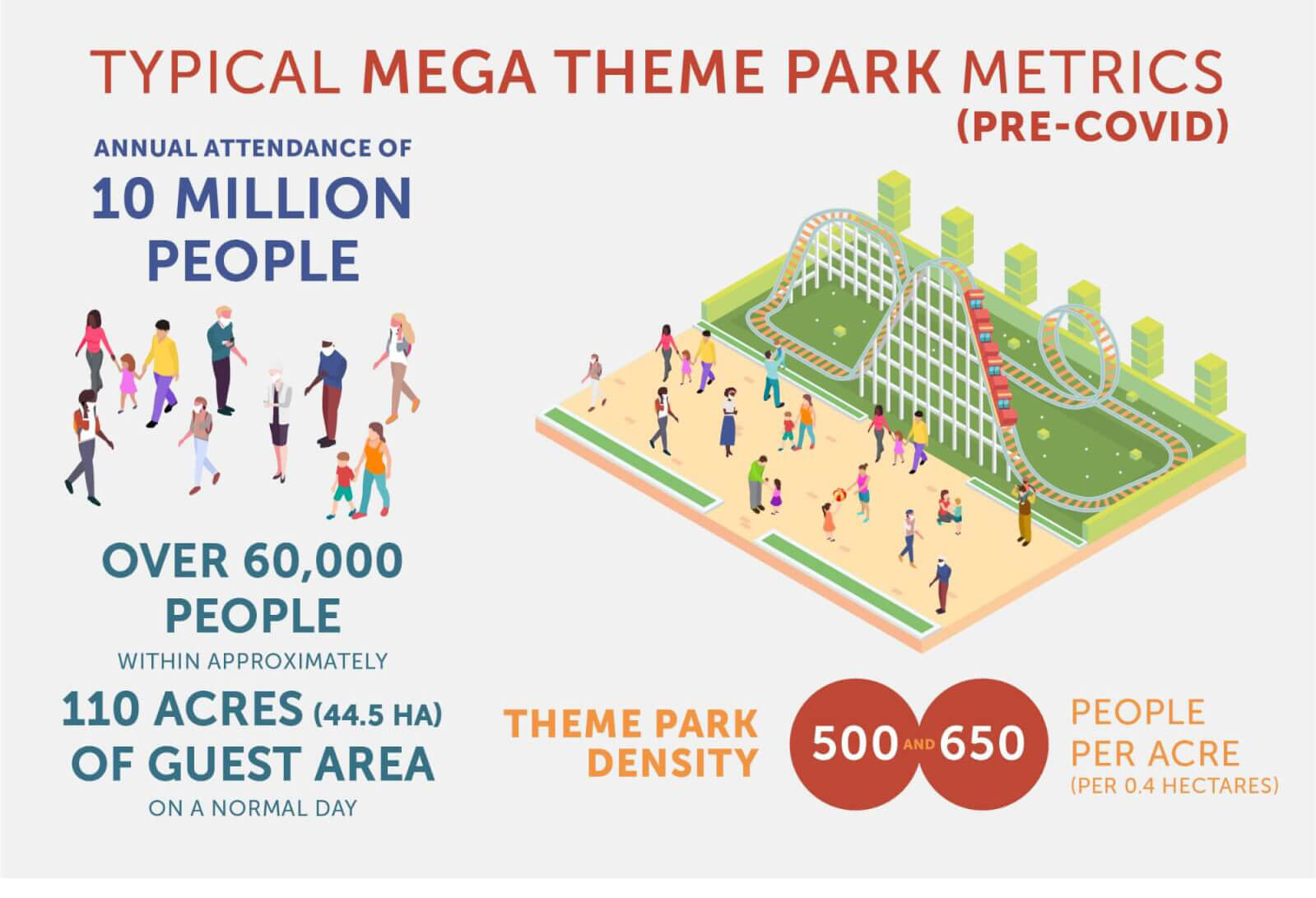

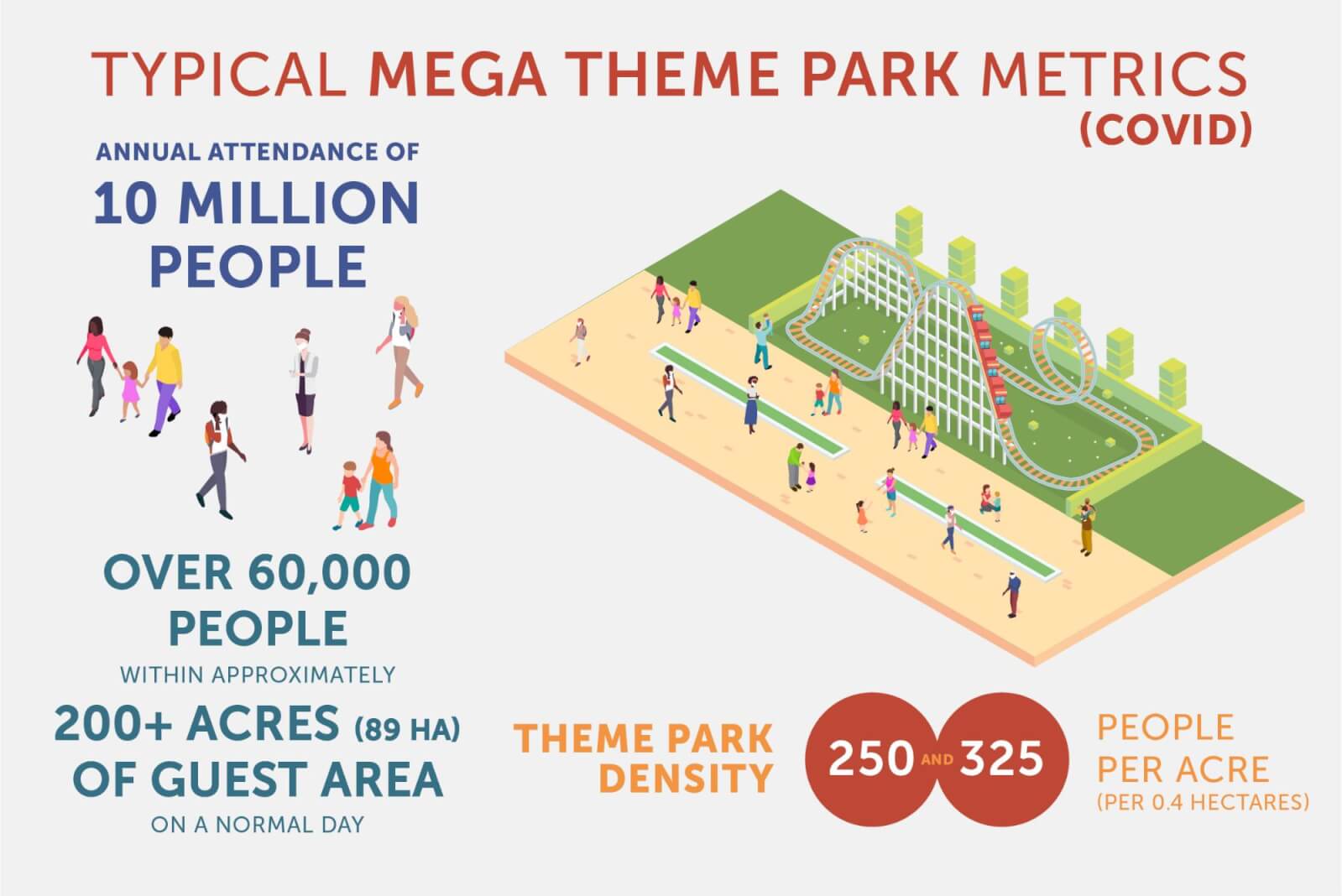

Disney Shanghai has opened its doors at reduced capacity to allow visitors space to learn the “new norms”, such as spacing out within a queue and frequent hand sanitizing and facility wipe downs. A “mega theme park” like the Disney or Universal parks typically means an annual attendance of over 10 million people, and over 60,000 people within approximately 110 acres of guest area on a normal day.

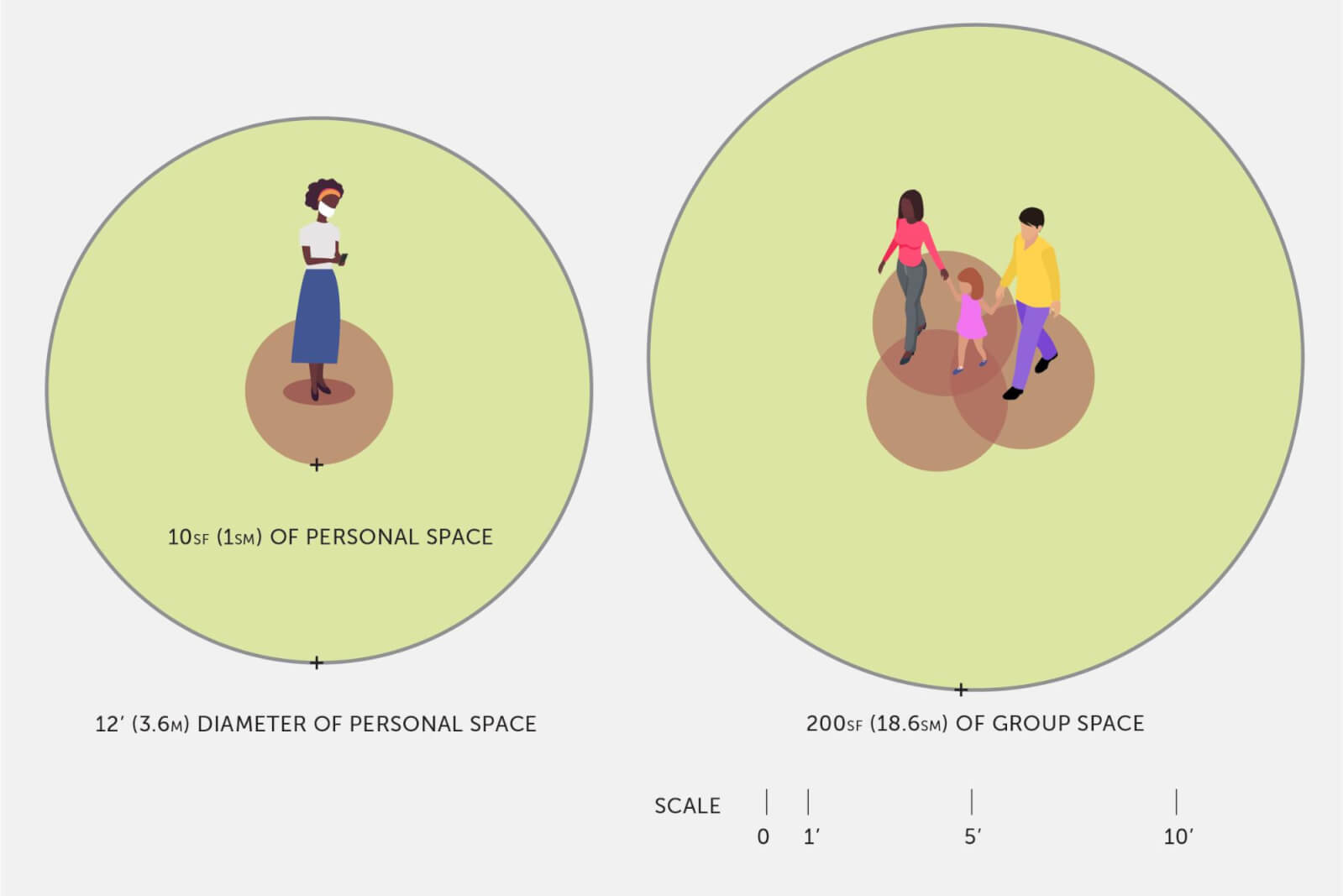

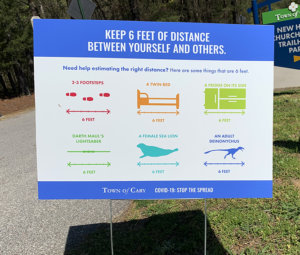

Disney Shanghai has opened its doors at reduced capacity to allow visitors space to learn the “new norms”, such as spacing out within a queue and frequent hand sanitizing and facility wipe downs. A “mega theme park” like the Disney or Universal parks typically means an annual attendance of over 10 million people, and over 60,000 people within approximately 110 acres of guest area on a normal day.  Space is the major commodity when talking about physical distancing. During a typical summer weekend day at a theme park, visitors often find themselves walking in a crowd, frequently having to stop momentarily or making frequent course corrections to avoid bumping others. This indicates a density of 10-15 square feet, sf (1-1.4 square meters, sm) per person within the circulation space, and if there’s a parade or a sudden character appearance, that density may go down to 5 sf (0.46 sm) per person, meaning that people will be brushing into each other and their movement will be severely restricted until the gathering disperses. These factors are what drive many theme parks to create “travel lanes” around parades or performance areas to allow the movement of people to still flow, albeit still at a reduced rate.

Space is the major commodity when talking about physical distancing. During a typical summer weekend day at a theme park, visitors often find themselves walking in a crowd, frequently having to stop momentarily or making frequent course corrections to avoid bumping others. This indicates a density of 10-15 square feet, sf (1-1.4 square meters, sm) per person within the circulation space, and if there’s a parade or a sudden character appearance, that density may go down to 5 sf (0.46 sm) per person, meaning that people will be brushing into each other and their movement will be severely restricted until the gathering disperses. These factors are what drive many theme parks to create “travel lanes” around parades or performance areas to allow the movement of people to still flow, albeit still at a reduced rate.

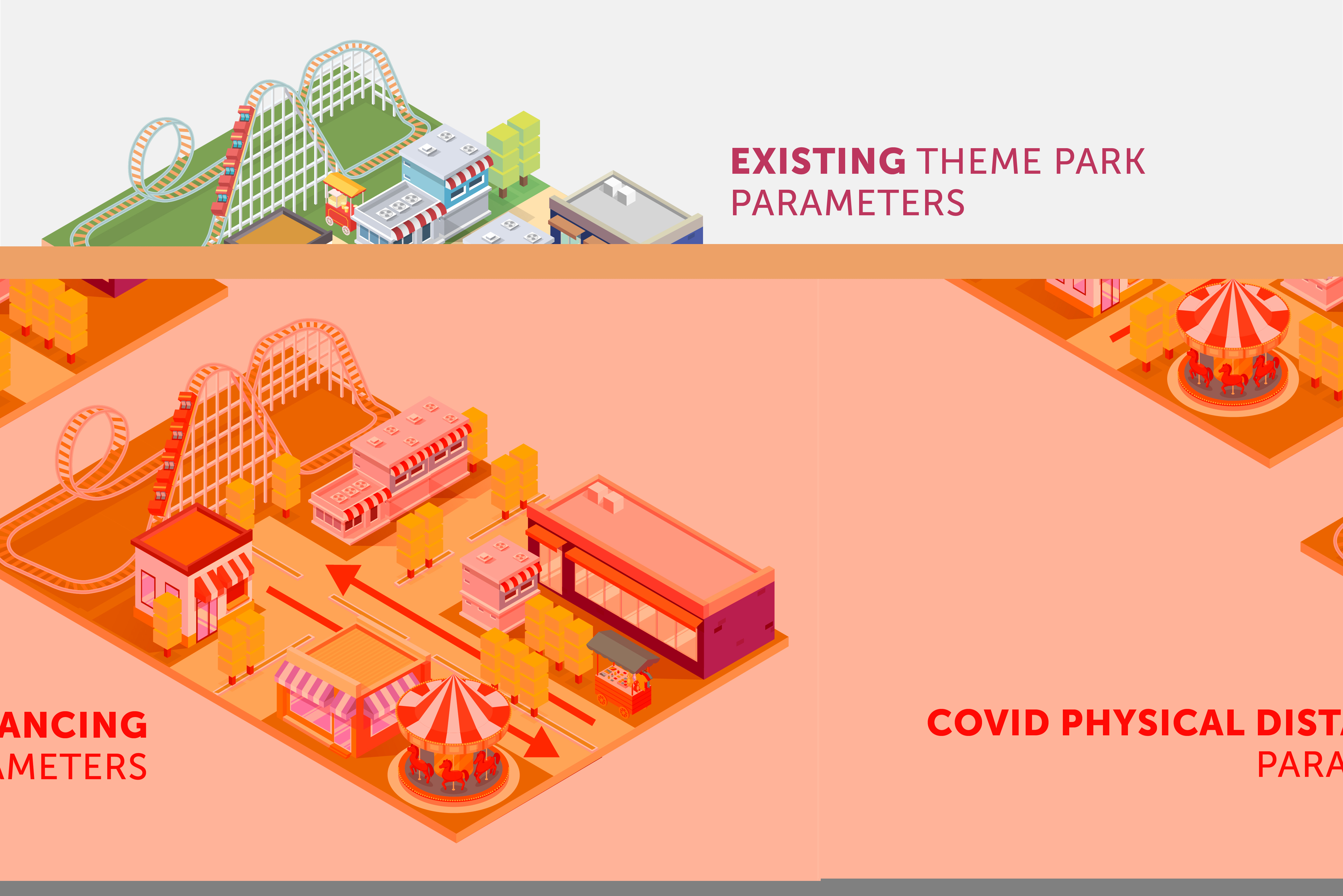

From a simple space planning perspective focusing on the physical distancing recommendations, the theme park circulation will have to increase 100%, the retail by 180%, food service by 150%, and attraction areas from 150-200%. These factors, applied to

From a simple space planning perspective focusing on the physical distancing recommendations, the theme park circulation will have to increase 100%, the retail by 180%, food service by 150%, and attraction areas from 150-200%. These factors, applied to

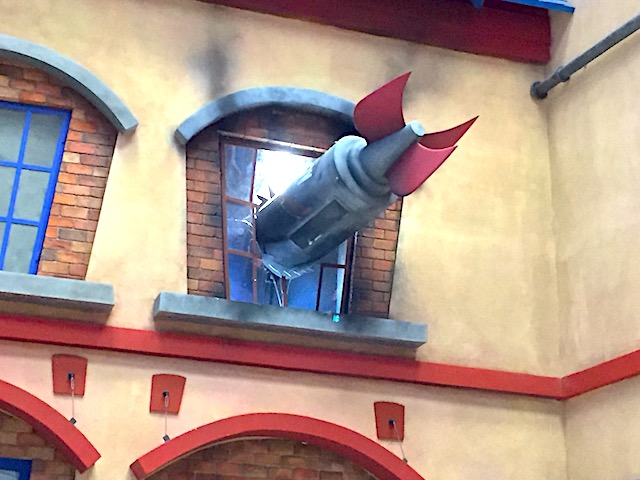

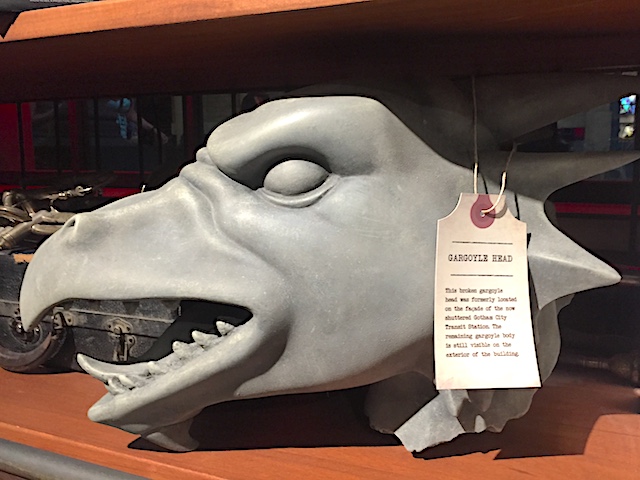

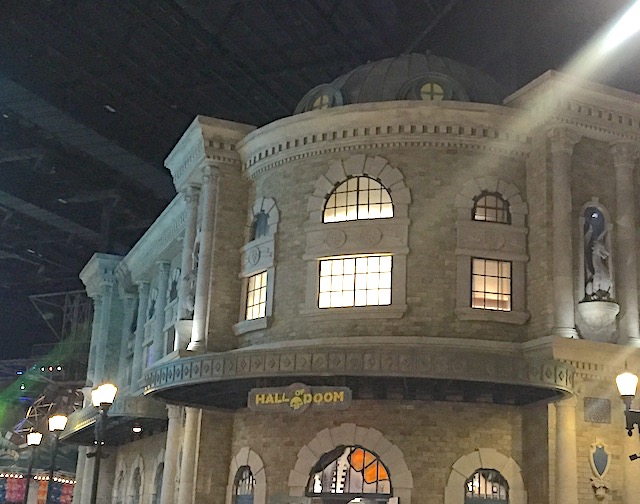

At Thinkwell’s

At Thinkwell’s

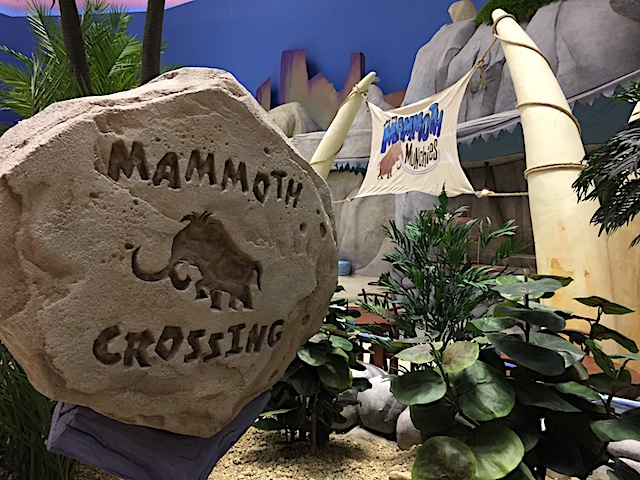

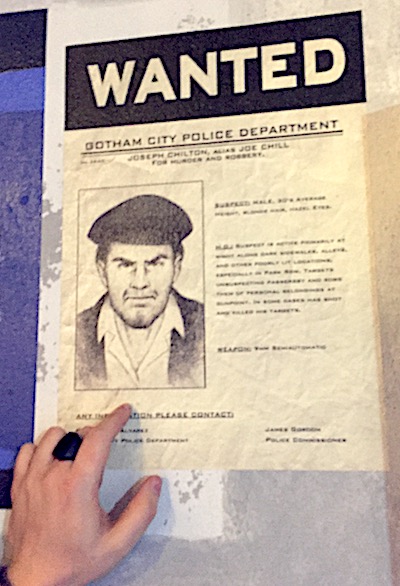

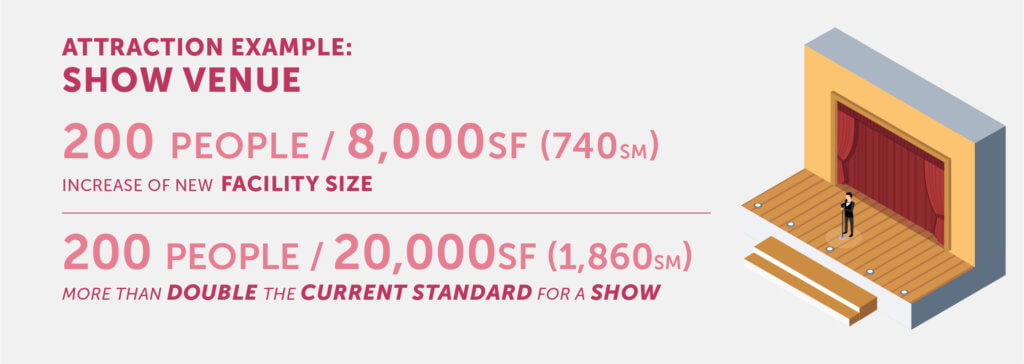

Take, for example, our

Take, for example, our

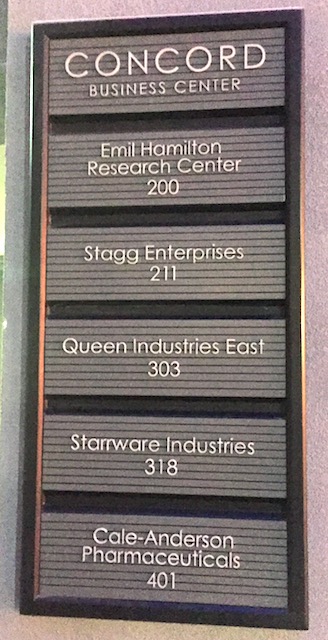

The Illumination of the

The Illumination of the